Solving LinkedIn Queens with APL

14 Jun 2025 on Peter Vernigorov’s blog

A couple months ago I noticed that LinkedIn now has a few simple games. They’re not much to write home about, but I really enjoy playing Queens.

This week I saw two posts about solving the Queens game programmatically. Both were quite interesting to me, so I thought this was a good opportunity to also solve the game in my favourite language - APL - and share my experience. Having been using APL for Advent of Code, I wanted to share my passion for it with others.

Rules

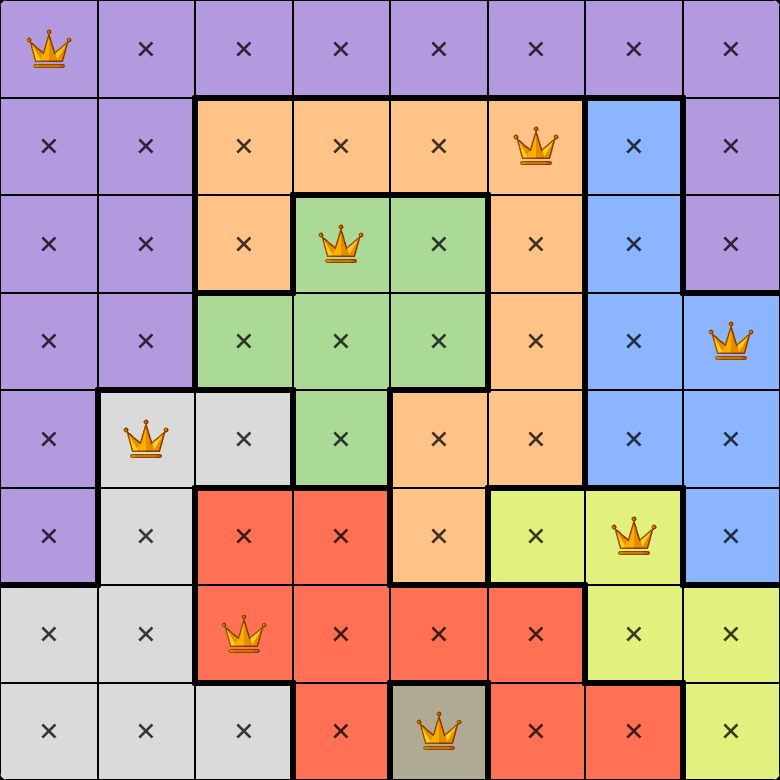

The game is pretty straightforward: each colored region must have exactly one queen, and two queens cannot occupy the same row, column, or be adjacent. Multiple queens may share diagonals as long as they’re separated by at least one space.

Board

First, let’s choose a data structure. LinkedIn sends the initial state as a list of rows, assigning each color a number. We will use 0 to mark queens. Let’s create a 2‑dimensional board representing the image:

b←⍉⍪1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1

b⍪← 1 1 2 2 2 2 3 1

b⍪← 1 1 2 4 4 2 3 1

b⍪← 1 1 4 4 4 2 3 3

b⍪← 1 5 5 4 2 2 3 3

b⍪← 1 5 6 6 2 7 7 3

b⍪← 5 5 6 6 6 6 7 7

b⍪← 5 5 5 6 8 6 6 7

And print it, by assigning it to the screen represented by a box:

⎕ ← b

1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1

1 1 2 2 2 2 3 1

1 1 2 4 4 2 3 1

1 1 4 4 4 2 3 3

1 5 5 4 2 2 3 3

1 5 6 6 2 7 7 3

5 5 6 6 6 6 7 7

5 5 5 6 8 6 6 7

Breadth-first Search

Next, algorithm choice: depth-first vs breadth-first search. While depth-first is a somewhat obvious choice (and works beautifully for N‑Queens, as seen in this video), I chose breadth-first search, inspired by a Sudoku solution video I love.

In our case, the search tree depth equals the number of colors. Each step expands the current solution space by enumerating valid queen positions for a new color. Here’s a simplified mock-up (color order is chosen strategically):

initial state

1 2 2 2 2

3 4 3 2 3

3 4 3 3 3

3 3 3 5 5

3 3 3 3 3

place all allowed queens for color 5

1 2 2 2 2 1 2 2 2 2

3 4 3 2 3 3 4 3 2 3

3 4 3 3 3 3 4 3 3 3

3 3 3 ♕ 5 3 3 3 5 ♕

3 3 3 3 3 3 3 3 3 3

place all allowed queens for color 4

1 2 2 2 2 1 2 2 2 2 1 2 2 2 2 1 2 2 2 2

3 ♕ 3 2 3 3 4 3 2 3 3 ♕ 3 2 3 3 4 3 2 3

3 4 3 3 3 3 ♕ 3 3 3 3 4 3 3 3 3 ♕ 3 3 3

3 3 3 ♕ 5 3 3 3 ♕ 5 3 3 3 5 ♕ 3 3 3 5 ♕

3 3 3 3 3 3 3 3 3 3 3 3 3 3 3 3 3 3 3 3

place all allowed queens for color 1

notice that solution space is shrinking as some positions are invalid

♕ 2 2 2 2 ♕ 2 2 2 2

3 4 3 2 3 3 4 3 2 3

3 ♕ 3 3 3 3 ♕ 3 3 3

3 3 3 ♕ 5 3 3 3 5 ♕

3 3 3 3 3 3 3 3 3 3

place all allowed queens for color 2, at this point only a single board is valid

♕ 2 2 2 2

3 4 3 ♕ 3

3 ♕ 3 3 3

3 3 3 5 ♕

3 3 3 3 3

place all allowed queens for the last color 3

♕ 2 2 2 2

3 4 3 ♕ 3

3 ♕ 3 3 3

3 3 3 5 ♕

3 3 ♕ 3 3

Let’s imagine we created an infix function fills that takes a color and current solution space, and produces a new solution space. We start with the board as an initial solution space, and fill color 5 with 5 fills b. Since APL is executed right-to-left, we can then fill color 4 with 4 fills 5 fills b. And so forth… the whole solution would be the result of 3 fills 2 fills 1 fills 4 fills 5 fills b.

For those familiar with functional programming, this will look like a use case for a fold, specifically foldr (right fold). In APL this is such a common operation that it is shortened to a single symbol - /. The above becomes fills / 3 2 1 4 5 b.

So far, we’ve been designing the solution using mock output and pseudo code. However, the top-level function for our actual solution will look very similar to the code we used, by first building that list and then folding it. In fact, here it is:

solve ← {0=⊃fills/(∪,⍵),⊂⊂⍵}

Let’s see how it works when built up slowly. Comments start with ⍝ symbol (a light bulb).

⍝ an anonymous function that just returns the argument

⍝ ⍵ is a symbol for the right argument

⎕ ← {⍵} b

1 2 2 2 2

3 4 3 2 3

3 4 3 3 3

3 3 3 5 5

3 3 3 3 3

⍝ flatten the board

⎕ ← {,⍵} b

1 2 2 2 2 3 4 3 2 3 3 4 3 3 3 3 3 3 5 5 3 3 3 3 3

⍝ unique list of colors

⎕ ← {∪,⍵} b

1 2 3 4 5

⍝ board again

⎕ ← {⍵} b

1 2 2 2 2

3 4 3 2 3

3 4 3 3 3

3 3 3 5 5

3 3 3 3 3

⍝ enclosed twice, making a solution space with one boxed element

⎕ ← {⊂⊂⍵} b

1 2 2 2 2

3 4 3 2 3

3 4 3 3 3

3 3 3 5 5

3 3 3 3 3

⍝ all together now, create a list that we will fold over as explained earlier

⎕ ← {(∪,⍵),⊂⊂⍵} b

1 2 3 4 5 1 2 2 2 2

3 4 3 2 3

3 4 3 3 3

3 3 3 5 5

3 3 3 3 3

⍝ actually fold using our fills function

⎕ ← {fills / (∪,⍵),⊂⊂⍵} b

0 2 2 2 2

3 4 3 0 3

3 0 3 3 3

3 3 3 5 0

3 3 0 3 3

⍝ disclose twice

⎕ ← {⊃⊃fills/(∪,⍵),⊂⊂⍵} b

0 2 2 2 2

3 4 3 0 3

3 0 3 3 3

3 3 3 5 0

3 3 0 3 3

⍝ pretty print the result

⎕ ← {'♕1234'[⍵]} {0=⊃⊃fills/(∪,⍵),⊂⊂⍵} b

♕ 2 2 2 2

3 4 3 ♕ 3

3 ♕ 3 3 3

3 3 3 5 ♕

3 3 ♕ 3 3

Helpers

Now we are ready to actually implement the fills function. But first let’s define some helpers.

The first helper is a place function that places a 0 (queen) on the board. It’s called like this: 1 2 place b. We will use an At operator, represented by symbol @:

⍝ ⍺ is the left argument

place ← {0@(⊂⍺)⊢⍵}

⎕ ← 5 5⍴1

1 1 1 1 1

1 1 1 1 1

1 1 1 1 1

1 1 1 1 1

1 1 1 1 1

⎕ ← 1 2 place 5 5⍴1

1 1 1 1 1

1 1 0 1 1

1 1 1 1 1

1 1 1 1 1

1 1 1 1 1

Easy enough!

Note: APL allows overriding index origin. The default is 1-based; however, the place function doesn’t work there for surprisingly complicated reasons - it involved the behaviour of Each with empty lists, prototypes, and @ primitive failing when asked to update index (0,0) in 1-based origin system. So this function assumes that the origin is setup with ⎕IO ← 0. The rest of the code doesn’t care about index origin.

Now, let’s build the function - we will call it avl - that returns valid queen positions for a specific color. We will call it with color and board as such - 4 avl b:

avl ← {

⍝ find positions of all existing queens

q ← ⍸0=⍵

⍝ find positions of a particular color

p ← ⍸⍺=⍵

⍝ boolean mask over p that have row or column conflict with any existing queen

rc ← ∨⌿1∊¨q∘.=p

⍝ boolean mask over p that are next to any existing queen

nx ← ∨⌿∧/¨1≥|q∘.-p

⍝ select color positions that are covered by neither mask using a Nor.

⍝ here slash symbol is a select, not fold

(rc⍱nx)/p

}

Last line in this function implicitly returns the result - list of legal positions for a queen in the color region. I leave deeper understanding of this function as an exercise to the reader. For those unfamiliar with APL primitives, APL Wiki has great pages for each, such as ⍸ - indices function.

And now we are ready to implement the fills function. We will split it into two functions - fills that works on a solution space and fill that works on a single instance of a board. Left argument for both is always the color.

⍝ places a queen on each available position of a board

fill ← {(⍺ avl ⍵) place¨ ⊂⍵}

⍝ calls fill for each board, then merged the results

fills ← {⊃,/⍺ fill¨ ⍵}

And that’s it!

Full Solution

The whole solution is this:

place ← {0@(⊂⍺)⊢⍵}

avl ← {

q ← ⍸0=⍵

p ← ⍸⍺=⍵

rc ← ∨⌿1∊¨q∘.=p

nx ← ∨⌿∧/¨1≥|q∘.-p

(rc⍱nx)/p

}

fill ← {(⍺ avl ⍵) place¨ ⊂⍵}

fills ← {⊃,/⍺ fill¨ ⍵}

solve ← {⊃⊃fills/(∪,⍵),⊂⊂⍵}

11 lines of code that have zero external dependencies, not even APL’s built-in libraries. Just the primitives. avl can be minified to much fewer lines, but I see no reason to do that.

There are heuristics that could be used, such as ordering colors by number of positions (fill smaller regions first). However, the current solution runs in a few milliseconds already. Still, there might be edge case boards where this solution doesn’t perform well, but I do not have many data points.

Let’s solve the large example:

⎕ ← board

1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1

1 1 2 2 2 2 3 1

1 1 2 4 4 2 3 1

1 1 4 4 4 2 3 3

1 5 5 4 2 2 3 3

1 5 6 6 2 7 7 3

5 5 6 6 6 6 7 7

5 5 5 6 8 6 6 7

⎕ ← {'♕.'[×⍵]} solve board

♕.......

.....♕..

...♕....

.......♕

.♕......

......♕.

..♕.....

....♕...

The End

My hope is that this has piqued your interest in APL, at least from the perspective of expanding your programming toolbox. APL is a very powerful language that allows you to express complex algorithms in a very concise way. If you want to learn more, I recommend checking out APL Wiki and TryAPL.

Discussion: lobste.rs news.ycombinator.com